Europe’s Valuation Discount: Opportunity or Trap?

Europe has long traded at a valuation discount to the US, visible across simple headline metrics such as P/E and P/B. What is more striking is that, even in 2026 and even after periods of strong performance in European indices, the discount remains wide enough to keep resurfacing in allocation discussions. So, the question is not whether Europe is “cheap” in relative terms, but whether the discount is beginning to look excessive in relation to the region’s earnings outlook and balance-sheet resilience, or whether it still reflects deeper, structural differences that are unlikely to disappear.

Disinflation in the euro area has progressed materially since the 2022 peak, with ECB commentary and official data highlighting a broad-based easing in price pressures as energy effects faded and goods inflation normalised. That trajectory has mattered for equities because it has allowed the ECB to move earlier on easing than many investors expected during the height of the tightening cycle. In principle, lower inflation and less restrictive rates can support equity multiples, but the link is indirect: valuation expansion is easier to justify when it is accompanied by an improving earnings path rather than simply a lower discount rate.

Europe’s index composition is central to why the valuation conversation rarely resolves cleanly. The broad European equity universe is more heavily tilted towards value and cyclicals (financials, industrials, consumer staples and energy) than the US large-cap complex (majority of which is technology and communication services). This matters because, in a world where investors have paid a premium for scalable, high-margin growth, Europe’s sector mix mechanically compresses index-level multiples and can dampen the optics of earnings momentum, even when individual European multinationals (luxury groups, healthcare leaders and advanced industrials) generate substantial revenues outside the region.

European firms have shown areas of resilience, particularly where pricing power and global demand exposure have supported margins through a choppy macro period. However, the structural constraints behind Europe’s lower valuation are well documented: weaker trend productivity growth, persistent barriers within the Single Market, and a financial system that remains more bank-based and nationally segmented than the US model, which can limit the speed at which capital reaches younger, higher-growth firms. Institutions including the OECD, the ECB and the IMF have been explicit that Europe’s productivity gap versus the US has widened over time and that scale, business dynamism and risk-capital depth are part of the explanation. They influence return on equity, reinvestment rates and the durability of earnings growth, which in turn shape what investors are willing to pay for each unit of profit.

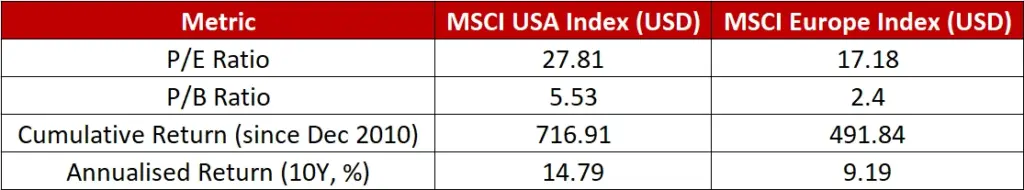

Valuation and Long‑Term Performance: Europe vs United States (Dec 2025)

Source: MSCI Inc., MSCI USA Index and MSCI Europe Index Factsheets, gross returns and fundamentals. All indices are in US dollars. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Data as of 31 December 2025.

Despite improved macro conditions and policy support in Europe, valuation and long‑term performance gaps remain visible. The MSCI USA Index continues to command a premium over the MSCI Europe Index across both valuation metrics and cumulative returns.

For investors, the implication is that “cheap” is a starting point rather than a conclusion. Europe may well look attractively priced relative to the US, but the case for a sustained re-rating depends on whether earnings growth can accelerate enough, and also remain consistent enough, to narrow the fundamental gap that valuations are reflecting. Over time, the market’s verdict usually rests on the quality of profits and the credibility of the growth path, especially in sectors where global investors have many substitutes.

A balanced reading, then, is that Europe’s valuation discount is real and visible, and the macro regime in 2026 has made that discount harder to ignore. But whether it is an opportunity or a trap depends on whether the region can translate stabilising conditions into sustained earnings delivery, not merely a temporary relief rally. The longer-term upside may still be capped without clearer evidence of improved productivity, deeper capital markets and stronger scale advantages in the parts of the economy where profits compound fastest. Cheap can stay cheap, and investors are usually better served by weighing valuation alongside resilience, sector mix and forward earnings power, rather than treating the relative price tag as a sufficient explanation in itself for investors.