What Are Liquidity Traps, and Why Do They Matter?

Japan, deflation, and low-rate environments explained.

You’ve probably heard someone throw around the term “liquidity trap” and just moved on. Fair enough, it does sound like one of those textbook ideas economists obsess over. But here’s the thing. It actually matters, and more than you might think.

A liquidity trap simply happens when interest rates are basically at zero and… nothing happens. People don’t borrow. They don’t spend. The economy just sort of stays stuck.

So, imagine a central bank cutting rates all the way down, expecting us to take loans, shop more, invest. But instead, people just don’t. They sit on their cash. Businesses hesitate. The whole system stalls.

That’s a liquidity trap. And central banks hate it.

Why Do Liquidity Traps Happen?

It usually starts with falling prices. That’s what economists call deflation. And if you think prices will be lower next month… well, why would you buy anything today? That hesitation spreads. People wait. Businesses hold off on new investments. Everyone tightens up. The economy, already slowing, starts to stall even more.

So central banks try to fix it the usual way by lowering interest rates. Sometimes all the way to zero, like it happened in 2020. That’s known as a Zero Interest Rate Policy (ZIRP).

But here’s the catch. In a liquidity trap, even free money doesn’t help. Rates are low, borrowing is cheap, and still people don’t borrow. They don’t spend. It’s like the whole system is frozen.

Why? Part of it’s psychological. When rates are that low, people assume the economy must be in bad shape. So they play it safe. They hoard cash. They wait. And this waiting keeps the economy still.

The Japan Example: Decades in a Trap

If there’s one country that knows this all too well, it’s Japan.

Back in the early 1990s, Japan’s economy hit a wall. A massive asset bubble burst – real estate, stocks, the works. BoJ stepped in and slashed interest rates to near zero. Later, they even dipped below zero. All the classic tools were used: cheap money, liquidity injections, years of patience.

But the economy didn’t bounce back the way they hoped.

Instead, Japan slipped into deflation. Prices kept falling, slowly but consistently. And with that, came hesitation. Consumers started saving more, thinking things might be cheaper next year. Businesses pulled back too.

Even with money flowing into the system, not much happened. Some economists called it like “pushing on a string.” You try to get momentum going, but nothing moves. This era is now known as Japan’s Lost Decades. Two, actually. Maybe more. A long stretch of weak growth, ultra-low inflation, and stop-start recoveries that never quite stuck.

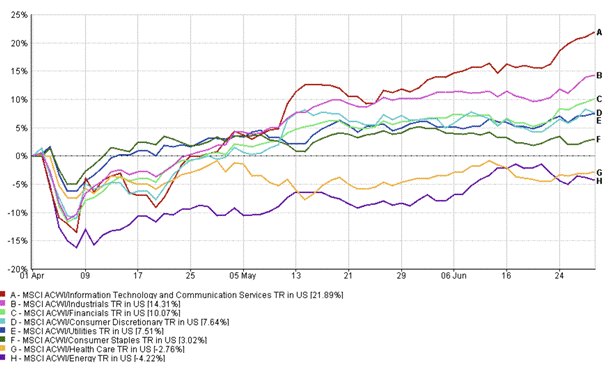

Japan’s Liquidity Trap: Interest Rates vs Inflation (1990-2025)

Sources: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development; World Bank via FRED®

This chart captures Japan’s long-term yields (blue line) and consumer inflation (dotted line). Since the early ’90s, yields have collapsed – but inflation remained near or below zero for decades. A textbook liquidity trap: cheap money, minimal movement.

Other countries took note. After the 2008 financial crisis, both the US and Europe acted fast to avoid the same fate. They cut rates, launched stimulus programs, printed money. And while it helped, somewhat, the fear of falling into a similar trap lingered for years.

So, Why Should Anyone Outside of a Central Bank Care?

Because in a liquidity trap, the usual tools — like cutting interest rates — stop working. The economy stalls. People aren’t spending, businesses aren’t investing, and the whole system just sort of… drifts.

For everyday savers, that might mean years of near-zero interest on deposits. For investors, it can push money into riskier places (like stocks or real estate) just to chase returns. And for governments? It means they might have to step in and spend big when central banks can’t move the needle alone.

In short, liquidity traps don’t just mess with policy. They shift how money moves through the whole system.

Bottom Line

A liquidity trap is what happens when money is cheap, but no one wants to spend it. Rates hit zero, confidence disappears, and the economy just… stalls.

Japan lived it. Other countries have gone close. The danger isn’t just low growth, it’s losing the usual ways to fix things.

And that’s why understanding liquidity traps matters. Because sometimes, the problem isn’t money. It’s fear.