Every time the economy wobbles or the stock market dives, the same terms get tossed around: recession and market crash. Sometimes, they even show up in the same headline – as if they’re interchangeable. But here’s the thing: they’re not.

One has to do with the economy at large – jobs, spending, production. The other? It’s all about the markets. They can overlap, sure. But they don’t always move hand in hand. Let’s unpack the difference, why people mix them up, and what all this means right now.

What Is a Recession, Really?

In plain terms, a recession is when the economy slows down – meaning people spend less, businesses scale back, and unemployment starts creeping up. It’s not just a dip in activity; it’s a broad, sustained decline. Economists often use two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth as a basic rule of thumb, but in the US, the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) digs a bit deeper. They look at things like wages, employment, production, and consumption to decide whether we’re officially in recession territory.

What triggers a recession? It’s rarely just one thing. Sometimes interest rates go up too quickly and borrowing slows down. Other times, prices rise too fast (thanks to inflation!), or an unexpected shock – like a war or a global pandemic – throws everything off balance. Most recessions are a mix of several pressures happening at once.

The US economy has experienced 12 recessions since World War II, with the average lasting about 10 months. The most severe – the Great Recession (2007–2009) – lasted 18 months.

So What’s a Market Crash Then?

A market crash is more of a sudden shock to investor confidence than a long-term economic slide. It’s when stock prices plunge fast – sometimes over just a few days. Panic selling kicks in, investors scramble for the exits, and volatility spikes. It’s loud, fast, and often quite dramatic.

Unlike a recession, which plays out over months, a crash can come and go quickly. But it still leaves a mark. It shakes confidence, wipes out wealth (on paper, at least), and can cause investors to rethink all their decisions.

Take a few examples:

- The Dotcom bust in 2000 hammered tech stocks, yet the broader economy didn’t collapse right away.

- In 2008, markets tanked as the financial system unravelled. That crash led into a deep recession.

- In early 2020, stocks plunged as COVID-19 spread – but the recession that followed was short-lived. During this time, the S&P 500 fell over 30% in just 22 trading days – the fastest crash on record!

So while crashes and recessions can show up together, one doesn’t always lead to the other.

Why People Mix Them Up

It mostly comes down to timing – and expectations.

Markets are forward-looking. That means they move based on what investors think is going to happen, not just what’s happening today. If people expect a recession, stock prices might fall in advance. And when signs of recovery appear, markets can start to bounce back – even if the economy on the ground still feels rough.

That’s why it often feels like markets and real life are out of sync. It’s not just noise. It’s baked into how investing works.

In fact, the stock market began falling months before official recessions were declared in 2008 and 2020 – showing markets move in advance.

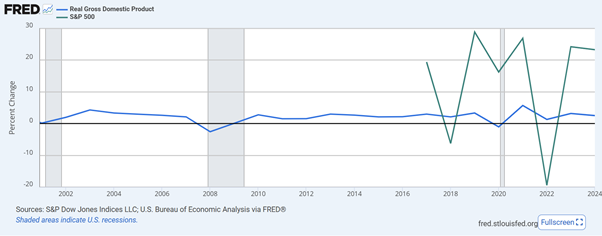

S&P 500 vs. US GDP Growth (2000-2024)

S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC; U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis via FRED®. Shaded areas indicate US recessions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Data as of 3 July 2025.

The stock market moves in sharper, faster cycles than the real economy. As this chart shows, S&P 500 returns often swing wildly from year to year, while real GDP growth tends to be steadier – even during recessions. That’s why headlines can feel more dramatic than the underlying economy.

Which One Hurts More?

That depends on your perspective. For most people, a recession is harder to ignore. Job losses, pay freezes, rising prices – these things affect day-to-day life. A market crash? It stings if you’re invested, but it doesn’t usually hit the average household directly.

Still, for investors, confusing the two can lead to poor decisions. Panic-selling during a crash might mean locking in losses right before a rebound. On the flip side, brushing off signs of an economic downturn could leave your portfolio exposed to longer-term damage.

Being able to tell the difference matters – especially when emotions are running high.

Where Do We Stand Now – Mid-2025?

So, here’s the big question: are we in a recession, a market crash… or neither?

As of mid‑2025, economic growth has slowed – but growth is still happening. The Bureau of Economic Analysis’s third estimate shows US real GDP fell by 0.5% (annualized) in Q1, driven largely by import spikes and weak consumer spending. And unemployment, while ticking up slightly, is still low at 4.1%. Inflation has eased but not vanished – core CPI is now around 3.1%, down from last year’s highs, but still above the Fed’s 2% target. Meanwhile, consumers are still opening their wallets: retail sales rose 0.2% in May, led by gains in travel and online shopping.

The stock market, for its part, doesn’t look panicked. The S&P 500 is up around 5-6% so far this year, while the Nasdaq-100 has gained nearly 8%, led by strong performance in AI and chip stocks. Over in Japan, the Nikkei 225 has been hovering near 38,000 – still well below its all-time high of over 42,000 reached back in July 2024, but firmly in positive territory. That’s not what a market crash looks like.

Central banks are starting to ease up too. The ECB just cut rates for the first time in years, and the Fed has held steady at 4.25-4.50% since late 2024 – a sign that policymakers are growing less worried about runaway inflation.

So while there are risks – sticky prices, geopolitical flare-ups, and global uncertainty – this doesn’t look or feel like a recession. And it certainly doesn’t resemble a crash. If anything, we’re in a phase of slowing but stable growth, marked by caution, not collapse.