As the dollar continues to depreciate, central banks around the world are facing a policy "tightrope walk". Since 2025, the US dollar index has fallen by more than 9%, triggering a chain reaction to the global monetary policy landscape. On the one hand, the weakness of the US dollar makes dollar-denominated imports cheaper, easing inflationary pressure; on the other hand, it also makes other countries' currencies appreciate, hitting export competitiveness, and thus triggering the policy dilemma of "whether to follow the depreciation".

According to Bank of America's latest global fund manager survey, 61% of respondents expect the US dollar to continue to weaken in the next 12 months, which is the most pessimistic outlook for the US dollar for investors in nearly 20 years.

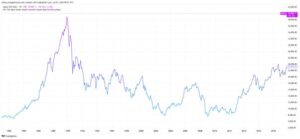

Driven by the weakening of the US dollar, safe-haven currencies such as the yen, Swiss franc and euro have risen significantly against the US dollar: the yen has risen by more than 10%, and the Swiss franc and euro have both risen by more than 11%. In addition, the Canadian dollar, Mexican peso, Polish zloty, and even the Russian ruble have all recorded appreciation to varying degrees. But some emerging market currencies such as the Vietnamese dong, Indonesian rupiah, Turkish lira and RMB are still at historical lows.

For most emerging markets, a weaker dollar is usually a "good thing": their large dollar debt burden is reduced, and the appreciation of their local currencies also makes imports cheaper, thereby reducing inflation and leaving room for interest rate cuts. Most central banks welcome a 10% to 20% drop in the dollar.

But this is not good news for all countries. Currency appreciation weakens export capacity, especially in the context of the Trump administration's new round of escalating tariffs, Asian export powerhouses are facing greater pressure. Asian central banks are particularly concerned about export competitiveness, and monetary policy will be very cautious. ”

In contrast, the Swiss National Bank is the most worried about the overstrength of its currency. The Swiss franc has continued to appreciate due to the inflow of safe-haven funds, which has affected its export-oriented economy. Analysts believe that if capital continues to flow in, the Swiss National Bank may have to take radical devaluation measures.

In Asia, India and South Korea may have room to cut interest rates, but Indonesia is not expected to cut interest rates rashly due to sharp exchange rate fluctuations and a large number of US dollar bonds.

Although "devaluation" can enhance export competitiveness in the short term, central banks are generally cautious. The depreciation of the local currency may aggravate inflation and at the same time incur trade retaliation or "exchange rate manipulation" accusations from the United States. Especially against the backdrop of increasing geopolitical tensions, central banks are more inclined to avoid "exchange rate wars."

In fact, the European Central Bank has already cut interest rates by 25 basis points in its April meeting, using the window of slowing inflation to stimulate the economy. Most central banks are still in a "wait-and-see" state, weighing the risks of devaluation against capital outflows and debt pressure.

Although devaluation is theoretically feasible, in the current environment, central banks are more inclined to avoid actively launching exchange rate wars, which will only bring more uncertainty to the global economy."